Last week, Andrew W.K. played a sold-out show at Cuisine En Locale while controversy swirled about tactics promoters use for up-and-coming area bands.

The controversy started when Boston band Trophy Lungs tweeted at W.K., saying that Keynote Company, the promoter, uses the pay-to play model. Keynote Company and W.K. subsequently confirmed that the show wasn’t using the pay-to-play model.

Hey @AndrewWK you’re playing for a Boston promoter that makes bands pay to play. Let us know if you want to drop off and play a real show.

— Trophy Lungs (@TrophyLungs) July 8, 2015

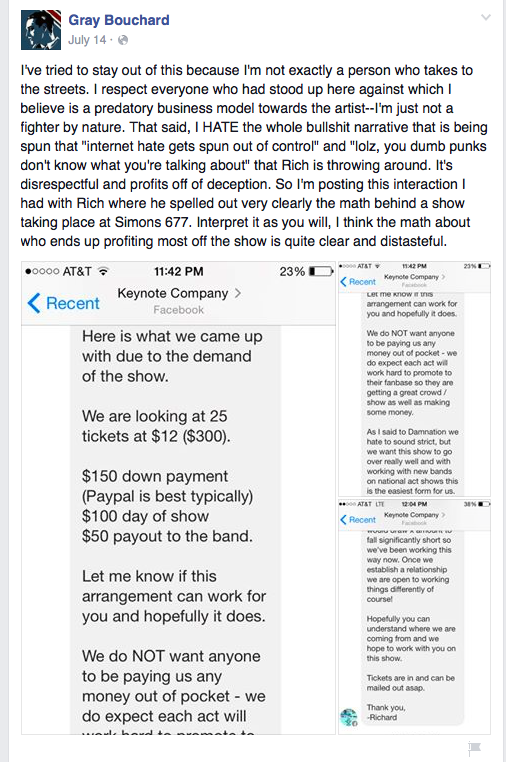

Pay-to-play comes in different forms, but the one often used and discussed is where a promoter requires a band to make a deposit and sell a number of tickets. One such example would be a band making a deposit of $100 to sell 15 $12 tickets, with the payout being the full $100 back, plus an extra performance fee. If the band can’t sell the tickets, they lose the money on the deposit. Such practice is not seen as illegal, unlike payola, the process of paying to influence factors like radio airplay. Pay-to-play even at play in playlist-making at music streaming sites like Spotify. However, many see it as an ethical quandary.

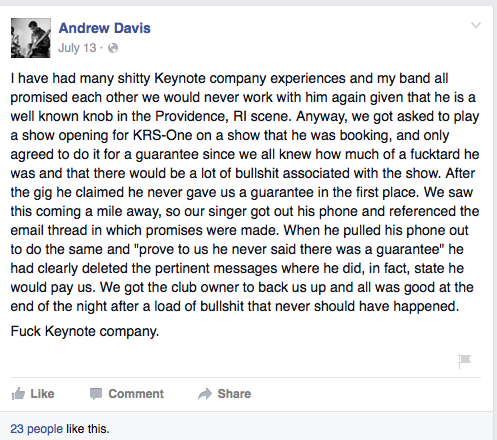

The show spawned a parody Facebook event page, with many of its attendees decrying pay-to-play. Its attendees are using it to discuss the controversy and point to other situations of pay-to-play:

By some, pay-to-play seen as minimizing the risk on behalf of the promoter and shifting a lot of said risk on up-and-coming musicians who haven’t built a large following. But others see it as an early investment, and financial risks grow as bands grow.

Richard Collier, who runs Keynote Company, said he understands the backlash to the practice.

“People seem to think all my shows are about only putting dollars in my pocket and nothing more. If I didn’t care about artists I wouldn’t be working with national touring acts – 8 years and 1000 shows later,” Collier told Allston Pudding in an email interview. “That was never meant as a brag, but clearly when you reach a volume you’ll have plenty of return base as well as some not. That’s true of any business.”

“Unfortunately, at some point in business … you grow and make decisions that don’t always appeal to everyone,” Collier said.

On Keynote Company’s website, it notes the model it uses through a particular FAQ: “Why are we asked to sell resale tickets to local / national shows and can’t we just get a door draw [a cut of ticket sales]?”

We’ve noticed since we’ve had bands sell tickets word gets out about the show. It also gives us a more direct correlation on who came out for what band. You sell tickets on local shows to get considered for national shows or future shows. The more you sell the better opportunities of getting more shows and on the national shows where the sales help us pay to bring in the bigger bands. It also helps to show them what our scene is capable of in regards to how strong of a draw the bands in this area have.

Roger Metcalf, manager of the Ruby Rose Fox band, says he has “mixed feelings on this, as I’m sure many bands do.”

“[Generally], this seems to be a deal that is presented to relatively new bands who, at the time of booking, may not have developed a proven ‘draw’—which is a kind of Catch-22,” said Metcalf.

“Performing live is not only an important component of building an audience, but also for improving musically,” he continued. “The conundrum here, of course, is that if, as a new band, you haven’t been able to play many paid gigs, then it’s unlikely that the band will have the finances to afford a ‘pay-to-play’ scenario without dipping into the pockets of the members of the band.”

While Ruby Rose Fox band has mostly avoided pay-to-play situations (and has not worked with Collier or Keynote), Metcalf offered insight as to why it may be good or bad for a band.

If bands look at it as an investment, he said, they must be careful about the gigs they choose.

“If the gig really is a good opportunity to play in front of new people who may like the music (and these do happen), and to develop musically, then I think taking gigs like this—early on in the progression of a band’s career—can make sense,” he said.

If bands factor it into a mix of mostly paying gigs, Metcalf said, they can look at the cost as a marketing expense. For instance, this scenario: Would $100 be better spent on a Facebook advertising campaign or paying to play a show?

W.K., who’s typically known for party-centric, overwhelmingly positive shows, is understanding of fans and musicians who feel disappointed by his recent Boston show.

“I totally understand why anybody would be upset or angry or have those problems,” he told Allston Pudding. “I understand if you don’t go to the show and I won’t take that personally at all. I want people to understand that I totally respect their feelings about their own bad experiences with those types of shows. I agree with that.”

For bands starting out, the pay-to-play model might seem like an early, costly obstacle. However, as a band grows in popularity, their costs will probably grow, said Metcalf.

“You might land a good paying gig, but then the club may expect you to promote the gig heavily (and you should), which means you’ll have costs for say, having a poster designed, printing posters, running an ad on social media, or maybe hiring someone to make a video, or hiring a photographer to improve your press photos,” said Metcalf.

“And after all that, you might still not draw, you might not cover your expenses (if it’s a door deal), and the club may not be interested in booking you again in the future,” he continued. “So there’s always an element of risk at every level, as every rock ‘n’ roll band is a (little or not-so-little) business. The stakes both financially and professionally get higher and higher the more you grow—and your mistakes will cost you disproportionately more than when you were smaller.”

In the initial wave of controversy surrounding the W.K. show, Keynote’s Collier talked to Boston.com about the practice. Since then, he says he’s received feedback through personal message and at shows from people involved.

“Moving forward I can’t say I will change the system, but perhaps tweaking will be in place and definitely will be paying more attention to our artists’ satisfaction,” Collier said.

Additional reporting by George Greenstreet. Contact the author of this post at jeremy@allstonpudding.com.