Adam Weiner is working a full time job plus overtime. Between releasing new music with Low Cut Connie (their sixth album Private Lives dropped yesterday), interviewing others – like Beyonce’s dad – and hosting his own livestream show “Tough Cookies,” he’s on the pulse of the moment and rolling with it.

Listening to Private Lives and watching “Tough Cookies” is like entering a time capsule, every lyric and word pulls you into a rich history. The band’s style of Rock’n’roll comes from sounds spanning the last hundred years with a heavy influence on the 1955-1964 pre British-Invasion years, one of many moments in rock history Weiner is “obsessed with.”

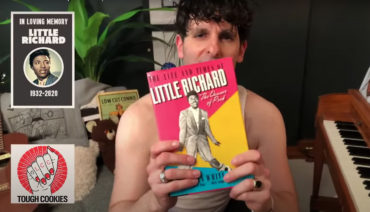

“Tough Cookies” and Private Lives entertain and educate, challenging us to question the history we’re given about music and culture. In the show, Adam interviews cultural icons that speak to homophobia, racism, and sexism in the music world and performs songs in tribute to those icons (with a torn tank top stripped down to his underwear). The album tells honest stories of the way people live in America today. Both cast a light on those who are overlooked, silenced, and excluded from society then and now.

When I caught up with Adam we didn’t just talk about history and music in the lens of the past, but what this moment means for the present and future of media, entertainment, and Rock’n’Roll.

Private Lives and “Tough Cookies” are like conceptual A- and B-sides of this 17-track double album. Unlike the traditional sense where the B-side is secondary, they go hand in hand. With stories of the unspoken, neglected, and hidden, both sides take us into the world of our private lives.

A-SIDE “TOUGH COOKIES”

…On The Importance of Sharing Music History

When I was 13 I got a record by Leadbelly and got obsessed with music from the ‘20s ‘and 30s – mostly Black music from the ‘20s and ‘30s. I was always out of my time. On “Tough Cookies” I’m doing a segment called “Songs from 100 Years Ago.” I happen to know a lot of music from then. I’m kind of obsessed with the history of the beginning of the entertainment business. 100 years ago was the beginning of the record business, the film industry, broadway, and radio. Television came later but we have a lot to reflect on. Because my show, “Tough Cookies,” is what I call a “Soul Music Variety Show,” it’s not a straight concert. It’s music, performance art, support group, all these things.

It’s the resonance around music. Early in the show, back in March, I started performing songs from the pre-Rock’n’roll era that had some bearing on the COVID crisis, the feeling of isolation. I noticed a really interested and curious response from viewers when I would do a song by Sister Rosetta Tharpe or Mississippi John Hurt or Bessie Smith. A lot of people had never heard the music, hadn’t heard of the artists, and because I am known as a Rock’n’roll artist and performer, I started to think from a musicological standpoint, it would be good if the people watching had a sense of where the music we play and perform comes from.

Once I started doing interviews and having conversations with people who have worked in the entertainment business, most of whom are Black, not all but most, I realized there was a bigger narrative here that we were putting together with the show about race in the music business.

That ranges from me talking to Darlene Love (of The Blossoms) about appearing on television in the early ‘60s, when The Blossoms had to wear this light shade of make-up, to my buddy Bobby Rush, who’s 86, about performing in the early 50s behind a curtain in a blues club in Chicago because the white patrons didn’t want to see a Black person. They wanted to hear the music but they didn’t want to see his face.

I started having these conversations and realized that we can entertain as much as we can educate. We can make musicological aspects entertaining for people.

…On Creating a Series where Entertainment Meets Education

After the murder of George Floyd, the whole format of the show changed. Up until that point what had been a “let’s all get through [quarantine]” performance, became a more activated experience. I switched the tenor and started to perform songs and speak more explicitly about issues in the country. I began to have more open conversations with some of my guests about racism, sexism, and homophobia in the music business of past generations.

Today I had a fabulous conversation with Jake Shears about homophobia in the music business and his experience. I had another great conversation two weeks ago with Beyonce’s father Mathew Knowles who grew up dirt poor in a shack in segregated Jim Crow south Alabama. He was driven to succeed and pass that drive along to his daughters.

I want to have these conversations so that the viewers are getting something active out of the experience. They’re learning, questioning their beliefs, and questioning the media and the history that they’ve been giving around music. Maybe, just maybe, they’ll enjoy music in a different way.

…On Segregation in The Music Industry and Rock’n’Roll

(in reference to the Hank Ballard and Etta James 5-track medley dialogue which Weiner performed in “Tough Cookies”)

There’s a few artists I’ve done a lot of songs by, but Etta James is one of my favorite singers of all time. With The Hank Ballard and Etta James piece, we’re talking about the early ‘50s. There’s two things that are interesting about this. 1) Supposedly we’re told Rock’n’roll started in 1955. Sometimes people are more generous and say ‘54, when Elvis broke through regionally with “That’s Alright (Mama).” Now I love Elvis but I would like to point out that records like this existed in the earlier part of the ‘50s.

Those records were called “race records,” a segregated part of the business. Black music on Black radio stations and Black stores for Black customers. Those artists, (and some of them were massive stars), didn’t have the opportunity to cross over to the top charts. It wasn’t a matter of taste. It was a matter of systematic segregation and censorship.

I like to shed light on people like Hank Ballard and the Midnighters and the early part of Etta James’ career. They were big stars in the R&B charts, in Black clubs they were legendary. They didn’t have the same level of ability to hit with the white masses as the white artists did—that came a couple years later. It also gives you a real appreciation for this period of music between 1955 and 1964 before the British invasion—these 9 years that I’m obsessed with.

Within those 9 years, you get this kind of coming together. White and Black kids were suddenly listening to the same music, they were listening to the same radio stations. Everybody loved Motown. Everybody loved Little Richard and Chuck Berry and Elvis. Chuck Berry got played on every radio station, Elvis got played on Black radio stations. There was this blend. We think today that we have a fully integrated situation in our entertainment and I seriously beg to differ.

…On How Genre Creates Barriers

The new kind of segregation is more about genre and corporate-mindedness. There isn’t a big mix of people all listening to the same music. It’s getting re-segregated. I’m trying to get people to look at things from another angle. If you’ve seen some of my interviews with these musicians, I ask a lot of them a very weird question. It always takes them by surprise and it’s somewhat awkward. I ask, “What genre of music do you feel like you were or are performing?” Seems like a simple question, but I always get a weird answer.

I asked this question a couple weeks ago to Dan Penn, a white country songwriter who wrote all these songs for Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett and Otis Redding. Everyone refers to him as a soul music songwriter. He told me, “I never heard the word soul until I was already 5 or 6 years into my career.” I said, “What kind of music did you think you were making?” He said, “I guess I would have called it rhythm and blues.” R&B. Sometimes I get the answer Rock’n’roll, sometimes rhythm and blues, or soul, or pop. These genre words that we live and die by now, they didn’t mean anything back then. It was just music. It was just music and it was good, that’s all people cared about.

The best example I can give you, and I said this on “Tough Cookies,” near his birthday in July – (he would have been 120 years old) – is Louis Armstrong. He’s one of the most important entertainers in entertainment history. He was not just the first Black international music star, he was really the first American international music star. There was no bigger star in recorded music before him. This is all the more striking because he was Black in the 1920s.

Musically he’s always referred to as the “father of jazz.” He would say “I never heard the word jazz until I was already famous.” They didn’t think what they were playing was jazz when he was coming up. They just thought it was music. He grew up in an orphanage in Louisiana with a mixture of Black, Haitian, Caribbean and white kids. They were taught songs from France. He learned to play his horn and all these French classical pieces from the 19th century. At the same time, he’s in New Orleans so he’s getting all this Caribbean and Haitian rhythm. Basically he took these beautiful lyrical French classic melodic styles and played it with a completely syncopated polyrhythmic Caribbean style. What he and his peers created is what we call jazz. It was a little bit classical, it was a little bit pan-african, to him it was just music.

[Armstrong] played his horn on some of the earliest what we now call country records, but at the time they were called hillbilly. He was friends with this guy Jimmie Rodgers who was the father of country music; he played his horn on his songs. Jimmy Rodgers’ first hit is called “Blue Yodle,” and he was yodeling over a guitar. So you’ve got this yodeling thing from the Swiss, with an Irish Scotch folk guitar thing, in a Mississippi blues format, with a white guy from Tennessee singing it, and a Black man from LA playing horn in it. I don’t know if you want to call that country or jazz or what, but to me it’s just revolutionary.

…On The Role of Music Today in America

There’s less of a public culture than we used to have. Our music industry is different than other countries in that we very much developed a ‘ticket purchasing culture’ over the last 15-20 years. There are very few places anymore that have a scene where people show up to see what’s going on musically.

If you could go back to previous generations, there were clubs, theaters… you just knew whatever was going to be there would be great. People would go on a Friday to dance. That’s what my parents’ generation did. Whether it was the Apollo Theater or some little divey bar in Philadelphia like the Uptown Theater, or a casino (say what you want about the improprieties of a casinos in Vegas or Atlantic City, but they used to have a great music culture).

We don’t have that as much anymore. I’ve been touring with Low Cut Connie now for 8/9 years and we have to build a fanbase. Then we try and get that fanbase to come and buy a ticket for the performance. There’s another show before or after us and their fans come in and leave. It’s a different kind of corporatized version of entertainment. It doesn’t inspire a lot of mixing of demographics or musical genres.

…On the Current Shift in Media and Entertainment

People ask me, “How is it going to be when you get back to doing your job?” I say, “I’m doing my job right now. I’m doing 2 shows a week, I happen to be doing them in my bedroom in my underwear, but I’m doing two performances a week.”

We have viewers in over 40 countries. It isn’t a full 7-piece band on a stage with lights and sound in a sweaty club, sure. The format of live streaming feels like the beginning of when radio showed up. People thought radio would be bad for the entertainment business because if you could turn on the radio and hear music for free, why would you buy it? That was the idea. A lot of musicians, especially jazz musicians, who were very famous in the 20s and 30s refused to appear on the radio or be recorded for a record because they thought people would steal their music.

It’s kind of crazy to think about that because radio really created the music business as we know it. It was a sea changer. There were people all about it and people skeptical of it. Live streaming is a similar moment. There are people who grab it with both horns and try to turn it into a new vibrant entertainment medium, there are people skeptical of it as a business, and there are people skeptical of it as an artistic form. They think it’s boring.

We hear this kind of debate every time a new shift happens in media. People thought films were a fad, and said “why would you want to see that when you can go to the theater and see real people?”

You get entrenched in a way of thinking about art and performance. When something new comes out it feels like a challenge, either people are up to the challenge or they feel like they are being challenged for their livelihood.

I’m totally inspired by the live streaming format. I don’t see it as a rival to live touring at all. I hope one day I do both.