Take a second look at the buildings that constitute our city’s urban fabric. Their past lives might hold unexpected histories of art and culture. If you’re eating chicken and biscuits at Sweet Cheeks— you’re also in the place of some of Boston’s greatest countercultural moments.

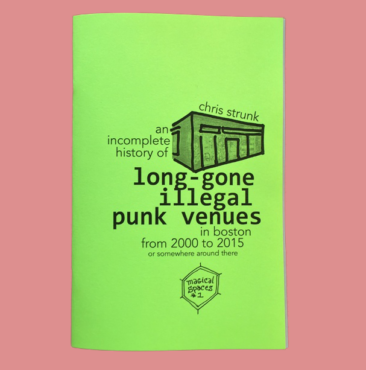

In the zine “Long-Gone Illegal Punk Venues,” written by Chris Strunk (musician/show booker/librarian), the reader is walked through over 40 warehouses, basements, garages, and studios that hid the DIY punk scene between 2000-2015. From the Polish Social Society in Dorchester to nondescript warehouses, you probably wouldn’t guess that these spots housed Boston’s evasive but raucous punk scene during 2000-2015. When attending one of these shows, a frozen turkey might’ve hit you in the head, a cloud of industrial dust could’ve enveloped you, and there was always the chance of a police run-in or two.

Strunk specifies that this is an incomplete list and that he specifically chose “long-gone notable illegal venues” (there were legal spaces too). Dispersed on both sides of the river, these spaces comprised a map of punk illegality. Behind walls and underground, there was once a world of noise.

The zine is important for many reasons. It serves as an incomplete record of the punk music scene while telling a larger cautionary tale about how subcultures are forced to create worlds behind walls when authorities are always shutting them down or silencing them. In the face of disinvestment, gentrification, and the pandemic, we’re losing countless venues and creative spaces with closure after closure. These spaces (which serve as cultural monuments) are built over, forgotten, and constantly threatened. According to Strunk, these stories need to be told before their memories and physical remnants disappear. If histories are preserved and fought for, maybe these subcultures that get pushed out and shut down can fight for their right to the city.

The first thing Strunk said when he picked up the phone was, “One second—I have to turn down the music.” That sentence alone set the tone for our conversation about a scene that’s constantly told to turn down the noise.

Allston Pudding: How did this project come about and develop over time?

Chris Strunk: I wrote it but it was a collaborative effort. Gilmore Kamney organized a Girls Rock Boston punk rock trivia night two years ago and asked me to write something about the punk scene. I thought to myself, what can I do that isn’t a big research project? I wrote the history of these spaces for that trivia night. That was the genesis of this zine and I guess it got put into Girls Rock Camp storage! Tim Devins had a copy and asked to re-publish. I added a bunch of stuff and re-wrote it.

When I started writing it, I thought it was good because these counterculture histories are important. It was good to do it now, as time goes on memories fade.

AP: Does the punk scene as you wrote it feel like an ephemeral chapter or something steeped in culture that will continue in different forms?

CS: The punk world directly ties into the past, what was happening before wasn’t different. The music and attitudes and trends changed but it is ephemeral in that there’s a lot of transience in Boston, more so than other cities. In terms of DIY music, it will continue. But now, during a pandemic and economic collapse we’ll have to see what the future looks like.

AP: The police and authorities are a huge part of the narrative you share. When thinking about ordinances and attitudes from the city there are serious implications for the survival of art and culture. How can scenes carve out space if the city doesn’t support them?

CS: That’s the million dollar question. No one really knows. Now we’re seeing not just illegal spaces are drying up from ordinances or gentrification, but the legal spaces are closing too. I’m optimistic that music will continue but I’m not sure what it will look like. If cities could provide spaces for people, that would be great, but the city doesn’t seem interested in funding DIY arts as we know them. They say, “What do you mean there’s no art scene? There’s Boston Calling; what more do you want?”

AP: You also talk about corporate approaches to house parties and underground music scenes, specifically places like Sofar Sounds. I hate to think startups are co-opting the idea of DIY and house shows.

CS: When SoFar came on, I thought it was my worst nightmare—The tech industry co-opting house shows for profit. But that will continue. People were still doing house shows all the way through the beginning of the pandemic—not as many, but they were still strong. I think of how these art communities can carve out space in Boston and, like I said, that’s the million dollar question.

AP: Right, especially with closures of studio spaces like the EMF building and Green St. Studios in Cambridge. There was a backlash of noise and movement surrounding those closures. There’s also the reality of marginalized communities getting pushed out; it’s all under the same systems.

CS: It seems like with EMF and in Cambridge, there were protests and meetings, but the city was like, “Maybe we’ll intervene… but no, we won’t.” Marginalized communities—that’s a whole other topic that I didn’t get into. That’s one of the problems. The scene I was involved in didn’t really reach out to marginalized communities. That would be an entirely different avenue to explore, especially in Dorchester and Mattapan. The history of that would be incredible.

AP: Can you explain how the outsider gets in? How did information and knowledge spread?

CS: Social dynamics changed depending on the venue, who was involved and how welcoming they were. Up until Operation Rolling Thunder, you could put the address on a flier and post it up around town and it would be fine. That’s how I started going to house shows. Over time, it became much more secretive and harder and more word-of-mouth. Show notices moved on to internet message boards. We had to be careful because cops made fake Facebook accounts to post in boards. When I was booking shows, if I got a message that seemed off asking for an address, I just wouldn’t respond to those.

There was one show when someone got hit in the face. The incident turned into this giant controversy that spilled into the local internet. Things became a bit more exclusive after that. I’m a librarian and I don’t “look punk” or anything, but since I was booking shows, I think I got a pass. There were some locations where people threw bottles at me and tried to weed out people that didn’t look punk. There were times it was open and welcoming, and others when it wasn’t.

AP: You talked about the tension between the mainstream and underground, how bands created their own performance spaces out of necessity, but also had to conform to industry demands at times when bands had to get booked at “legitimized legal spaces.”

CS: It did turn a corner at some point. Here’s one example: I was involved in booking a show in 2012. When I looked at the lineup, it was so great and everyone wanted to be a little more famous. The whole set happened because we had to go through their booking agent. There was a turn when things got more professional around that time.

AP: That’s pretty ironic and contrary to how the scene formed against the mainstream initially.

CS: Right. At first, you couldn’t book a punk show with a club if they weren’t interested. The only way to pay touring bands was to have it in a house.

AP: What about cover charges? Did it vary by location? How did it hold up economically?

CS: *Laughs* A cover charge depended on how adamant you wanted to be about charging. For the most part, sometimes houses took a small cut. You would try to collect as much money from people at the door as you could but people weren’t always cooperative with paying. Most money went straight to bands. It wasn’t that complicated.

AP: It’s interesting how the experience of a punk show is so different from other live music experiences. Like being against stages.

CS: Sometimes there were small stages in the basement, but basically everyone was on the same level. In the early 90s people thought bands shouldn’t play on stages because they shouldn’t be as “above.” Everyone is on the same level. But of course you couldn’t see everything.

AP: You also bring up the Ghost Ship fire in Oakland, CA and how that changed people’s perspectives in thinking about danger and risk.

CS: When Ghost Ship happened, everyone who was spending time in these spaces thought, “Oh my god. I could have died or killed someone.” It was a real ‘woah’ moment that people hadn’t thought of before.

AP: Who have you distributed the Zine to so far? What’s the plan?

CS: Tim Devin will handle most of the distribution. You can order the zine from Tim and it’s distributed by Printed Matter.

Lastly, I encourage anyone involved in counter cultural arts and music scenes to document the scene as it’s happening or in its recent past before someone from outside documents it and gets it all wrong or memories fade.

[Long-Gone Illegal Punk Venues by Chris Strunk is published by Somerville’s Free the Future Press and available for purchase through Printed Matter.