Photo Credit: Hannah Dixon

Few circumstances have changed the last time we spoke to K Nkanza. In Allston Pudding’s last interview with the talented multi-instrumentalist behind “queer metal” project Spring Silver, the COVID-19 pandemic raged on as K released “Plead Insanity,” the first single that followed their 2019 album The Natural World.

Nearly a year and a half later, K has just released their sophomore album as Spring Silver: the punchy blend of pop and alternative rock that is I Could Get Used to This. But even with the passage of time and the release of multiple singles from the record, much still remains the same with the global pandemic that loomed over our last conversation.

Despite that, I Could Get Used to This has a glut to dig into on its own — from its frequent pivots in genre and sound, to guest spots from names like Bartees Strange, ex-New Englander Sad13, and local cellist JB Fulbright of Prior Panic. Shortly before the album’s release, we chatted with K Nkanza about the variety of styles, experiences, and approaches that went into I Could Get Used to This.

This is fun because we’re following up on the last time I interviewed you, which was for the first song you released from this album. It kind of brings things full circle.

Yeah, it’s crazy ‘cuz that was quite a while ago. For a good while, I was like, “I really need to release the album in lieu of just these singles coming out.” And then I was like, “Wait, that was like a year ago. That was a substantive amount of time.”

That was fall 2020, yeah. It feels weird to think it was that far back. It felt far more recent than it was. Time is fully disappearing in this pandemic.

Yeah, I was like, “How come the momentum from the album hasn’t built from those singles?” And then I realized, “Oh wait — people probably thought they were one-offs for like a good nine months.”

Looking back at our last interview, though, one of the things we spoke about last time was how you navigate different genres and sounds in your work as Spring Silver. How did that affect putting everything together with I Could Get Used to This?

This album is a lot more streamlined. Because of the pandemic, I was like, “I have to put something out with a little more of a sense of urgency.” And I felt like, if it was more concise, then that would come across. I realized this album is about half the length of the last one. [Laughs]

I also feel like that also applies to me incorporating various genres and trying to fit the sonic textures I was doing on the first album, and trying to fit that into a format that was a little more concise — trying to fit it into pop formats without sacrificing the vastness of the project.

In relation to that, one of the other things we talked about last time with “Plead Insanity” was the inclusion of Sadie Dupuis and Bartees Strange as guests on that song. The guest contributions on that song were just vocals, but on I Could Get Used to This, the features are all over the place. What did those additional contributions bring to this album for you? And do you feel like it’s another way of incorporating different sounds and artists you’re influenced by?

To answer the second question first: yeah, I think so. I also think it’s a way to maintain a conversation with the outside world — which, at times, can feel like a struggle when you’re in quarantine. Just having other people contributing their voice, literally or artistically or both, makes a real difference on the album. I’m still pretty protective when it comes to guitar and bass; I feel like, with that section of the song sonically, I’m still like, “That’s gotta be me.” [Laughs] I said this last time, but you can’t really fake different singing voices on a track. It’s just going to be a markedly different thing than if you just put a distortion effect or if you sing from far away. It’s something you can’t replicate.

Outside of that, I have a really deep love for string sections and arrangements. There was an opportunity to work with Daniel [Sohn], who did the arrangements on a few songs — I had to take it. Daniel’s a friend of a friend, he worked on Max Gowan’s release Last Companion, and I [thought] those arrangements were mind-blowing. Max was just like, “You can hit him up.”

But, to tie it back to where I started, the fact that I had the opportunity to work with different people like Daniel or Harlow [Diggs] or my friend Kylan [Hillman], it felt like something I absolutely had to take. It makes a real difference. Whether it’s small or big, it makes a genuine difference in some way.

Do you feel that keeping your guitar and bass parts as they are and bringing these new players/arrangers to this album expands what the sound of Spring Silver is while still keeping it definitively yours?

Yeah, I think so. A lot of the parts I sent out to people — depending on the song and the parts — may have been parts I wrote or arranged. That wasn’t always the case, but sometimes I would have the drum part down to a tee in MIDI and then have someone else play it and add a few things. But I feel like that expands the world in some way [that wouldn’t be there] had I kept the MIDI drums.

I feel like I could make an album where it’s me on drums — where it’s entirely me. I probably would need help from Ananth [Batni] with the mixing to get it to where it sounds. But once you go down that route, I feel like you become self-conscious or a lunatic. I’m not the greatest drummer or anything, but once I’m like, “It’s gotta be me,” that’s where the problems start. It’s taking away from me just being like, “How can I make this the best song that I can?”

Sometimes it’s also freeing to let someone else in on it. It can be something where someone can take something in a direction you’re not even thinking.

Some of the songs would just sound much different if it were just me. One of the things with Spring Silver is that, even when it’s “all me” on the programming or the instruments, it’s me trying to make it sound like it’s not. That’s kind of the whole thing. Like, even when it comes to singing, I’ll try to switch up my vocal performance. Anything to make it feel like the horizon has expanded a bit.

To jump off what you were saying with the string arrangements, “Saymour’s Stop” is maybe the biggest stylistic shift on the album and comes right at the record’s midpoint. How did you decide on that sound compared to the rest of the album and on its placement?

It’s like the end of “Side A,” if vinyl ever happens. Because having “O Kristi” as the beginning of “Side B” [makes] the album start off again with a big hit. In my opinion, “Saymour’s Stop” is a somber note to end that side on, which connects to [the similar sound of] “Call It Strength” at the very end of the album. I’m kind of trying to create that sort of arc twice on the proverbial sides [of the record].

Since you mentioned starting “sides” strong, let’s dip into the first single you released specifically for this album cycle: “Little Prince.” Was it a similar decision to start big that led you to put it right at the start of the record and release it along with the album announcement?

Yeah, that was it. I’m not even sure what I would have gone with for an alternative. I feel like that one’s such a strong opener. Maybe “O Kristi” [as an alternative], but like I said, that’s kind of the start of the second half. So “Little Prince” was a “best foot forward” sort of thing. I really like all the songs on this album, but that one — from an accessibility standpoint — is probably the most accessible thing I’ve ever written in my life. The sort of energy and the “field recording” of the New Year’s Eve party from college make it as perfect an opener as I could probably muster.

How did that chatter make its way onto the song? Was it something where you just wanted the song to have that as a buffer?

I don’t think that was the initial intent, but once I decided on it, I was like, “That’s a cool buffer.” I also felt like it was weird to have only one vocal intro thing on “Set Up a Camera.” I felt like it would’ve been weird if all of the other songs had started normally and then I have the one Beastars sample.

But I was writing “Little Prince” back in 2017 or 2018, and I thought it would be cool to have people clapping on it. But the song was upbeat and we were super drunk. [Laughs] We couldn’t do it fast enough! We’d be like, “One, two, three, four!,” and we’d just get slower and slower. I had the metronome on it and we just couldn’t fucking do it. [Laughs] So at one point, on a whim, I was like, “Oh my god. We’re clapping to the tempo of this song, which is markedly slower to the song I had written, so I’ll just put that in.”

To jump to another of the singles, the latest one, “I Saw Violence,” is one you’ve said is about a real thing you witnessed right in front of you. Can you talk about that and how it became the song it did?

When I was at UMBC, they tried to basically sneak Melania Trump onstage to talk about a D.A.R.E. sort of thing for kids from the neighboring high schools, and the way we found out about it was through the news. They weren’t going to tell us because they knew we’d be pissed. So I went to the on-campus chapter of the DSA that was planning a protest and, when we went, it was crazy. We would be protesting and chanting and some of the high school kids who were filing into the event center were [cheering for us]. There were cops everywhere because it was Melania Trump.

Then a dude in a MAGA hat came in and said he wanted a “civil debate,” and then very shortly after punched someone in the nose. They were fine, but it was one of those things that sounds like it was made up by an AI. Like, “It’s not like a Trump person is gonna come up, say they want a civil debate, and then punch you in the face. That’s so on the nose.” No pun intended. It just sounds so strangely contrived. Later on, the UMBC chief of police Paul Dillon was like, “Nah, that didn’t happen.” He said it was staged and then he also said it didn’t happen. I don’t know if those two things necessarily coincide.

I was just pissed and I wrote lyrics about it. I don’t think I had the song yet — as I talked about last time, I’ll write lyrics or poems and then I’ll fit it to a song. [Then] I came up with the guitar part and [thought] it tonally fit together really well.

Moving from something very lyrically-driven to something decidedly less so, I want to talk about the instrumental “Light Tread” toward the end of the album. How did that one come to be and how do you think that fits in with the rest of the album?

I thought it might be a nice respite, especially since it’s sandwiched between two high-tempo songs that were released as singles. I came up with the [riff] back in 2017 and I was like, “That’s really nice.” I’m constantly writing riffs and progressions and recording them and putting them in folders. And so I’ll browse and find recordings and demos and stuff like that. That’s how I unearthed what I had for “Plead Insanity” [before completing it]. I feel like [“Light Tread”] and “Saymour’s Stop” are nice breaks from things that are a little more upbeat in tempo. I thought it was cool to have something unabashedly pretty as opposed to an intense beat or emotive wailing. [Laughs] Just something that’s genuinely very tranquil.

Since you brought it up, to further bring things full circle from our last interview, one thing I noticed listening to “Plead Insanity” for the first time on this album was that it’s a different mix from the single release in 2020. Could you break down how you tweaked it from the single release to the album version?

I always had the intention of putting it on an album. So when I released it, I was like, “Well, I can just continue to work on it until the album comes out — not rush it as much, make it cleaner.” I really just prefer this mix quite a bit. I switched out some guitars and added some new ones in. The original release was mastered by Ananth, who is really good at mixing and mastering, but the album one was mastered by Dan Coutant, whose whole thing is mastering. That’s one thing that’s markedly different: it has a less compressed sound. With that in mind, I was like, “How can I capitalize off this by making something that has a fuller guitar sound?” Especially on the chorus, there are more layers of guitar.

I don’t listen to my music that much, because sometimes it can be a strange experience. But it’s nice to be able to continue working on something you’ve released as a “finished product” and then be like, “Well, I can continue to work on it knowing how it sounds right now” in a way you can’t necessarily on something that isn’t “finished.” I think it’s cool to have this evolution where you can listen to that and “Set Up a Camera” and see the differences — see how they were changed, in my opinion, for the better. You get more time to reflect and see how you can work on it further.

Speaking of “Set Up a Camera,” can you talk about the development of that track and deciding to release it in early 2021? And what got tweaked on that track since you last released it?

The drums are quieter. The drums on the original version are very loud… like VERY loud. One thing that’s kind of funny is that I made this tweet that was me playing one of the guitar lines where you can hear it within the context of the song. I sometimes make covers or videos of me playing my songs, and it’ll be DI-ed so it doesn’t sound like an unplugged electric guitar [recorded] through a camera. But either way, I used bits of that in the newer version.

Maybe this is just one of my OCD things, but when a song isn’t on an album, it kind of irks me a little bit. Which is kind of funny now because albums matter less than ever, but in the back of my mind, when I was working on “Plead Insanity” and “Set Up a Camera,” I was like, “These are gonna be on an album.” Like, there will be these rougher versions where, because the song is “finished,” I might as well release it and build hype. Which eventually died down because it’s been over a year. [Laughs] But I figured I might as well put it out there. And then you can hear a newer, adjusted version on the album. I guess if you listen a little more with the notion that there are changes, you can hear some of them. But the changes are definitely less drastic than they are on “Plead Insanity.”

Each of the songs on this album seems to deal with its own focal point, but what are the common conceptual or lyrical threads you were drawn to for this record?

I think the main throughline, as I experienced it when I was making most of this album, was a feeling of isolation and being kind of unhinged. [Laughs] I feel like that’s what I’ve been trying to put forth with this album: trying to express the feeling that quarantine and the numerous other things outside of that brought about. I think that’s where some of the urgency comes from. There is a lot of that [on] The Natural World, but there was also me just feeling around to see if I could make an album at all. With this one, I was like, “I can, so I can pack a punch with this one and express where I’m at.”

It sounds like the circumstances definitely played a hand in this album’s sound, compared to the more open feel of The Natural World. Does that sound right?

Yeah, that and — a lot of people would scoff if I called myself old, so I won’t — I feel like, when you’re making an album between the ages of 19 and 22 is different from when you’re 25 and all you’ve done for the past two years was sit in your room. I just felt like I should probably make this happen, not even necessarily from a success standpoint, but just [in terms] of going for it musically. Just trying to make something that is immediate and an expression of where I am.

Similar to how The Natural World sounds a lot like it’s title, I Could Get Used to This is very indicative of what this album sounds like. How did you decide on that title?

I really like this title. You hear a corny line in a movie where someone is like on a beach and someone else is serving them a pina colada and they’re like, “I could get used to this!” [But instead] it’s you in your room in quarantine or you in the service industry concerned about whether you’re going to get sick or dealing with anti-maskers. All of these things that you will basically have to get used to. So it’s kind of like that tension and the irony of “I could get used to this miserable thing I’m going through.” And maybe it’s also a question of “Can I get used to this?” It’s a little bit Radiohead-ish, where they’ll put something innocuous and you’ll have to be like, “…oh!”

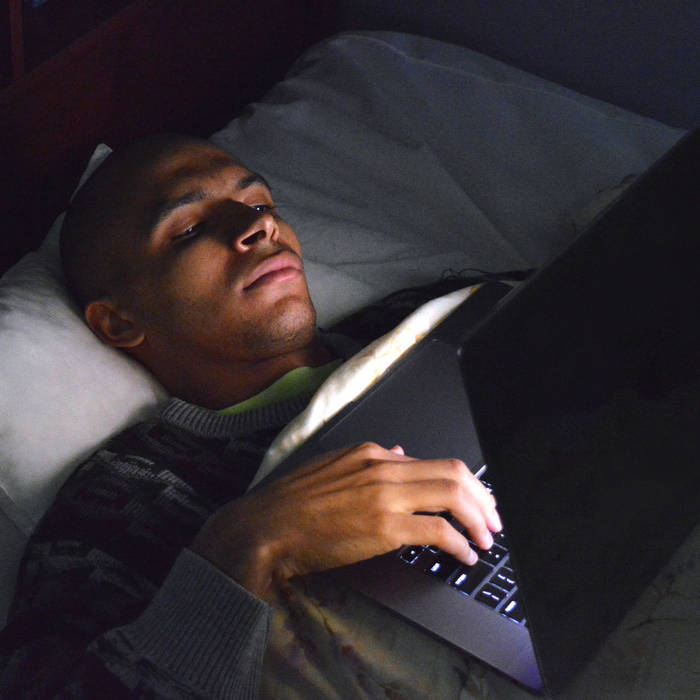

You start to think about the other layers of irony beneath it, yeah. I also think of the ironic implications of you pairing that with the album cover of you passively staring at the laptop.

Yeah, you just get into that habit of taking crazy information just lying down.

In its own way, it ties into where we left off last time we talked. Especially recently, it feels like nothing has changed. It’s just that more of it has happened.

The title is almost a question of “Can you get used to this?” or “Have you gotten used to this?”

It feels very appropriate that this album has been percolating as long as it has, because it still feels relevant as it’s coming out.

As I was working on it and things were supposedly getting better, I was like, “Will it still be as potent?” It was a dumb thought and a dumb concern for a thousand different reasons. Like, not only will the quarantine and the pandemic be over by the time the album’s out, but we will have no problems on Earth. [Laughs]

Yeah, if anything, the question next time it comes to make an album just becomes, “What changes next time? Is there more of all this? Will there be more to be urgent about?”

Yeah, it’s just [a question of], “What urgent things this time?” [Laughs]

Spring Silver’s new album I Could Get Used to This is out now. Stream the album below via Bandcamp.